Classical music can seem intimidating. It’s easy to view it as a musical form most suited to the ivory tower, reserved as it often is for concert halls. Not to mention that it is so frerquently treated as sacrosanct in comparison to more popular musical forms. But this often has less to do with the music itself than the atmosphere created around it.

The Silly Symphony series by Disney provide a perfect example of why. The cartoons made use of classical music, stripping the genre of its pretensions and placing it squarely in the world of popular entertainment.

The brainchild of Carl Stalling, the series helped revolutionize animation and is even responsible for rival studio Warner Bros. creating its Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies series.

Springtime was the third film in the Silly Symphony series. Last week, we delved into the music of Edvard Grieg and Franz von Blon that appeared in the short, but they weren’t the only two pieces of classical music featured. Viewers were also treated to Amilcare Ponchielli’s “Dance of the Hours.”

Dance of the Hours

A little over two minutes into the short, a rainstorm explodes on the scene pouring water onto the earth below. A tree bathes and dances in the shower before getting struck by lightning. We then see a pair of mushrooms that are revealed to be serving as umbrellas for two grasshoppers. As the last few drops of rain fall, the grasshoppers close their “umbrellas” and begin to dance. The music continues to accompany the action as the grasshoppers are eventually eaten by a frog, who then begins using cattails to recreate the melody and rhythm on the shells of turtles.

The music accompanying their frolic is a portion of Ponchielli’s “Dance of the Hours.” Those of a certain age will likely instantly recognize the tune as being the melody to Allan Sherman’s 1963 novelty hit “Hello Mudda, Hello Fadduh (A Letter from Camp)” as well as its sequel, “Return to Camp Granada” (released on 1965).

Over the years the piece has been lovingly parodied and referenced in countless works. In 1940, Disney would again make use of it by including its entirety in a segment of the film Fantasia. A few years later, Al Sherman (father of Disney Legends Richard and Robert Sherman) would use segments of the piece for the song “Idle Chatter” which was recorded by the Andrews Sisters.

Disney’s treatment of the song in Fantasia is of particular note because it is simultaneously a parody of classical ballet and a celebration of the art form. Disney animators used ballerinas as reference for their animation, including including Russian prima ballerina Irina Baronova.

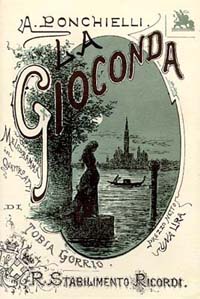

The “Dance of the Hours” was written as a short ballet for the Act 3 finale of Ponchielli’s opera La Gioconda, which originally debuted in 1876. It had been commissioned two years prior by Giulio Ricordi of Casa Ricordi, a music publishing firm founded in 1801.

Born in 1834 in Paderno Fasolaro, Italy, Ponchielli earned a scholarship to the Milan Conservatory at the age of 9 and wrote his first symphony by age 10. A few years after leaving the conservatory he would compose his first opera, and would publish his second opera (I Promessi Sposi) when he was only 22. Despite this, he would not find any true musical success until he revised I Promessi Sposi in 1872 at the age of 38.

For La Gioconda, Arrigio Boito was asked to write the libretto with Ponchielli providing the music. However, Boito would write the text using the pseudonym Tobia Gorrio, an anagram of his actal name. The opera’s first performance was held at Teatro alla Scala in Milan, though Ponchielli would continue to revise the piece until 1879, when his fourth and final version debuted.

Ponchielli died seven years later at the age of 51, and the majority of his works would go unremembered (despite immense success during his lifetime). However, La Giaconda continues to be regularly performed and “Dance of the Hours” has become instantly recognizable, even to those generally unfamiliar with the opera.

To Offenbach or not to Offenbach?

While researching this blog post, I came across several references that suggested that the short also incorporates music from Offenbach’s Gaîté Parisienne, a classic ballet perhaps best remembered for its lively can-can.

Based on my own personal viewings of the film and consulting with others who have watched it, I was unable to identify any music from the ballet within Springtime. While I could be mistaken, due to an inability to find any specific reference to which piece from Gaîté Parisienne was used, or where in the short it may have appeared, I have decided to leave it out. Should I find any more detail in the future the substantiates the claim, I am happy to revise and include notes on the piece.