Neil Gaiman, paraphrasing G.K. Chesterton, once said, “Fairy tales are more than true, not because they tell us that dragons exist, but because they tell us that dragons can be beaten.” It’s a sentiment that might have been expressed by Walt Disney, the man most responsible for keeping so many classic, European fairy tales (albeit in sanitized form) in the collective consciousness during the 20th century.

Peter and the Wolf, an animated short originally released as part of the 1946 anthology film Make Mine Music, seems to perfectly capture Mr. Gaiman’s statement. The story follows a young boy, Peter, who sets out to capture a dangerous wolf armed with nothing more than a pop gun. As in most fairy tales, he doesn’t undertake the journey alone. Joining him on the quest are a bird, a duck, and a cat. Against the odds, this motley crew manages to capture the wolf, surviving the dangers of the deep, dark woods.

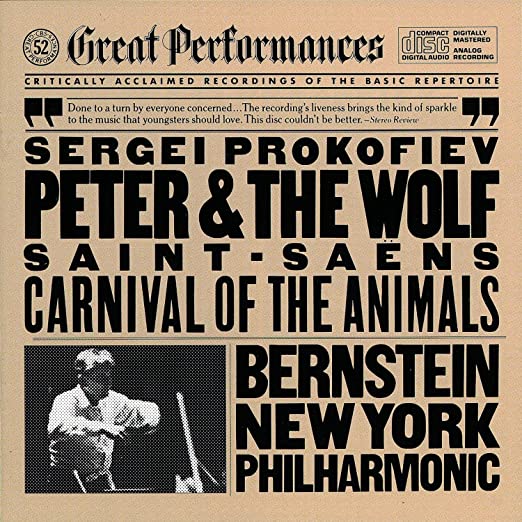

The music, written by Sergei Prokofiev, brilliantly uses melody to carry the story along, with each character being assigned a “theme” featuring specific instruments. This served not only a dramatic, narrative purpose but also helped educate young listeners about the various instruments in the orchestra. As Prokofiev later explained, “In Russia today there is a great stress on the musical education of children. One of my orchestral pieces (Peter and the Wolf) was an experiment. Children get an impression of several instruments of the orchestra just by hearing the piece performed.”

The character of Peter is represented by a jaunty section performed by the strings. Listening to it, you can picture Peter traipsing happily through the woods. A clarinet provides the slinky voice of the cat, while the waddling duck is depicted through an oboe. A flute is used for the bird, the airy sound flitting about from note to note, while the stodgy grandfather is represented by the bassoon. Then there is the wolf, whose menace is shown through a trio of French horns playing a minor progression.

Put together, the music moves the narration along, mirroring the rising and falling action of the story, alternating between moments of pastoral beauty, whimsy, and tension. This cinematic progression of the music was no doubt aided by the fact that Prokofiev had written scores for films.

The blend of education and whimsy must have appealed strongly to Walt Disney, whose own creations often took a similar approach. To get a sense of this, one only needs to turn on one of the old Disneyland television series (with its segments like “Man in Flight” and “Man In Space”), the True Life Adventures Documentaries, and films like Donald In Mathmagic Land.

Of course, the roots of Disney’s Peter and the Wolf go back further than any of those projects, with the earliest seeds being planted in 1938 when Prokofiev and Disney met in California. But that story cannot be properly told without a brief detour to learn a bit more about the composer.

The Prodigy

Born April 23, 1891, Prokofiev was born into an agricultural family. His mother came from a family of serfs owned by the Sheremetev family. It is, perhaps, a curious twist of fate that this barbaric economic reality may have played a role in giving us the works of Prokofiev. It seems that the Sheremetev’s provided the children of serfs with education in theater and the arts. His mother Maria became a rather adept amateur pianist, in love with the works of Beethoven, Chopin, and Anton Rubinstein.

As a very young child, Prokofiev would listen to his mother play the piano, enamored by the pieces she performed. He took quickly to the instrument, composing his first piano piece at the age of five. Four years later, he wrote his first opera.

He was accepted into the conservatory at St. Petersburg, after a recommendation from the composer Glazunov. He attended the school from 1904-1914, but his natural talent led him to find the education boring. As a result, he developed a reputation as a somewhat arrogant student. During this time, he developed an active interest in musical innovation and took inspiration from artists in a number of fields (such as Pablo Picasso, various modernist Russian poets, the theatrical philosophy of Vsevolod Meyerhold, and the work of Sergei Diaghilev, who helped revolutionize Russian ballet).

His early compositions were not particularly well received by the public. An article on Classic FM notes that he earned, “notoriety with a series of difficult works for his instrument, including his first two piano concertos. The second caused a scandal at its 1913 premiere. The audience reportedly left the hall with exclamations of “The cats on the roof make better music!”

By 1917, he’d written his first symphony, typically referred to as the Classical Symphony. Prokofiev stated that it was loosely based on the style of Joseph Haydn. Britannica notes that this was a creatively fertile period for the young composer. They note, “When Tsar Nicholas II was overthrown in February 1917, Prokofiev was in the streets of Petrograd, expressing the joy of victory. As if inspired by feelings of social and national renewal, he wrote within one year an immense quantity of new music: he composed two sonatas, the Violin Concerto No. 1 in D Major, the Classical Symphony, and the choral work Seven, They Are Seven; he began the magnificent Piano Concerto No. 3 in C Major; and he planned a new opera, The Love for Three Oranges…” the last of which would become his most successful operatic composition.

He then entered an extended period of time spent abroad (with the sanction of the Soviet government), traveling to locations like San Francisco, New York City, Paris, London, and even the Bavarian town of Ettal. It was during this time that he met and married singer, Carolina Codina, and completed The Love for Three Oranges. He also composed, among other things, an opera called The Fiery Angels, ballets like Le pas d’acier and The Prodigal Son, several symphonies, and other orchestral works

A sense of homesickness brought him back to the Soviet Union. Once home, he again entered an incredibly fruitful period, composing his Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor, the ballet Romeo and Juliet, and music for movies such as Lieutenant Kije.

In 1936, he wrote “a symphonic fairy tale for children”, which would become beloved around the globe.

Peter and the Wolf

Natalya Sats, director of the Children’s Theater in Moscow, commissioned Prokofiev to produce a pedagogical piece that would educate children about the various parts of an orchestra. As noted in a 2004 essay by Brad Weismann, “The official culture of the day in the USSR was socialist realism, a style that featured idealistic depictions of the common man, depictions that were mandated, reviewed, critiqued, and censored by the central government. A useful work of art taught a moral lesson and reinforced Soviet values. For a libretto, Prokofiev started with a rhyming narrative by popular Soviet children’s writer Antonina Sakonskaya, about a Young Pioneer (the Soviet equivalent of a Boy Scout) challenging an adult mired in reactionary, pre-Revolutionary thinking.”

Prokofiev did not care for the text, instead providing his own, the story of a young boy who sets out to capture a wolf. Not merely a charming fairytale, the piece was also intended to instill Soviet-era virtues. A 2018 article from Classic FM relates, “Natalya Sats had another lesson she wanted to communicate: a lesson about the battle between youth and right-thinking (Peter) and the inflexible representatives of the old world (Grandfather) who did not understand the new Soviet ideology. Peter and the Wolf is a story about not being afraid, about taming nature and conquering external threats. The dark shadow in the woods beyond the fence perfectly evokes the paranoia of the Stalinist Regime, which wanted Russian citizens to believe that they “live in paradise, but there’s always an external enemy just beyond the fence, for which they must be on guard”.”

Of course, the message of a dark and unknown wilderness that poses unknown threats is hardly unique to Soviet propaganda. It’s been at the heart of fairy tales around the world. In many cases, used to reinforce the idea that danger awaits those who wander outside of the prescribed norms embodied by the values of the community, a rather different message than that provided through the story of Peter. In its own way, it does mirror some of the tales of man conquering nature, a sort of expansionist or colonialist concept that the wild can be subdued through progress. What that progress looks like, of course, is contingent on the values of the culture that creates the story.

To the average Russian listener, the story must have conjured a wealth of contradictory emotions. As the BBC noted in an analysis of the piece, “It is outwardly “apolitical”, but all too clear in its message. The original Peter was to be a Pioneer, one of the dawn-facing youngsters who would go on to join the Komsomol – the Soviet youth organization in Stalin’s new Russia. But surely when children shuddered at the line “If a wolf should come out of the forest, then what would you do?” their parents must have looked anxiously at one another. There, in a single rhetorical question, was their day-to-day dilemma. Living in an isolated giant, with a fascist wolf just to the west, a circling group of hunters in the Western democracies, and a secret police who turned up so regularly to knock on doors that the majority of thinking Russians (and certainly Shostakovich after “Muddle Instead of Music”) kept a “little suitcase” packed and ready by the front door.”

Curiously, for a piece that was born of Soviet Russia, it was a trip to America and a meeting with a man who might be considered the quintessential capitalist, Walt Disney, that helped give Peter and the Wolf some of its lasting fame.

The Magic of Disney

Walt Disney released the world’s first feature-length animated picture, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, in 1937. It was a film that immediately grabbed the heart and imagination of Prokofiev, who was said to be so enamored of the film after his first viewing that he wanted to see it again the very next day.

Peter and the Wolf had debuted a year before, and the following year found Prokofiev traveling to the United States and Los Angeles, where he would play the piece for Walt Disney. It’s a meeting that would later be recreated in the 4th-anniversary episode of Walt Disney’s Disneyland (with the role of Prokofiev performed by composer Ingolf Dahl, who closely resembled him).

As Walt narrates in the film, “I remember how his fingers flew over the keys of our battered old piano. How his face glistened with perspiration as he concentrated on the music. And all the time I could see pictures. I could see his lovely fantasy coming to life on the screen.”

Sadly, World War II interfered with production. Disney became fully devoted to creating work for the war effort, such as training films, insignia for various crafts, and even propaganda-style cartoons.

With the end of the conflict, Disney returned to making movies with the sole intent of entertaining, and Peter and the Wolf found itself included in Make Mine Music. The segment was narrated by Sterling Holloway (best known now as the voice of Winnie the Pooh, the Cheshire Cat, and The Jungle Book’s Kaa). As in the original, the piece starts with an introduction of the various themes, and the characters they represent, letting the listener and viewer know which instruments are associated with which character.

The story remained generally faithful to Prokofiev’s original, with a few exceptions. Disney gave the duck, cat, and bird names, and also gave names to the hunters. In addition, Peter was already aware of a nearby wolf, whereas in Prokofiev’s piece Peter is simply warned of the possibility of a wolf by his grandfather. The inclusion of the young boy heading off to hunt the beast armed only with a pop gun was another invention not found in Prokofiev’s text. Disney also gave the tale a slightly happier ending. In the original, the duck is swallowed whole by the wolf, and the audience is told that if they listen closely they can still hear it (a pretext for repeating the duck’s theme at the end). In Disney’s version, the duck is thought dead, only to be discovered alive.

Sadly, by the time Disney made the film, Prokofiev was back in Russia and there is no indication that he was aware that the film was made.

A Lasting Legacy

By a cruel twist of fate, Prokofiev’s death occurred on the same day as that of Joseph Stalin. Crowds of people filled the streets to mourn the death of the dictator, rendering it impossible for Prokofiev’s body to be taken out of his home for burial. He remained there for three days.

Even the newspaper paid scant mention to his passing, with it being noted on page 116. The 115 pages prior to that were devoted to Stalin. As noted in a Houston Press article, “Adding further insult, no musicians could be found to play the great composer’s funeral. Every musician of any note was ordered to perform at Stalin’s funeral and the various surrounding festivities. Prokofiev’s family was reduced to playing a recording of the funeral march from his ballet Romeo and Juliet.”

Fortunately, time has a way of correcting these things. While the name of Joseph Stalin has become reviled around the globe, that of Prokofiev has only grown in stature. Composer Arthur Honegger declared him, “the greatest figure of contemporary music.” During his life, the great composer Shostakovich said of him, “I wish you at least another hundred years to live and create. Listening to such works as your Seventh Symphony makes it much easier and more joyful to live.”

Eighty-six years after its original composition, Peter and the Wolf continues to delight and inspire audiences. Performers as diverse as Viola Davis, Alice Cooper, David Tennant, David Bowie, Leonard Bernstein, David Attenborough, Sir Peter Ustinov, Carol Channing, and Itzhak Perlman have performed the narration for the piece. Numerous adaptations have been made for film and television (including a Sesame Street interpretation with Elmo as Peter).

After being released as part of Disney’s Make Mine Music, it was reissued as a stand-alone short and was later released on home video. The episode of Walt Disney’s Disneyland that featured the dramatization of Walt and Prokofiev’s meeting was included in the Walt Disney Treasures release “Your Host Walt Disney: TV Memories (1956-1965).”

Prokofiev once said, “In my view, the composer, just as the poet, the sculptor or the painter, is in duty bound to serve Man, the people. He must beautify human life and defend it.” He would be happy to know that his music continues to live on, inspiring those who hear it, carrying them away into rhapsodies of beauty and imagination.